The emergence of spring wildflowers is getting a lot of attention now, but insects are getting active too. I’ve seen several butterflies and moths flitting around (unfortunately I was not able to get IDs). When we see spring beauties (Claytonia virginica), we also notice bees on them. Likely these are spring beauty mining bees (Andrena erigeniae) that are specialists of this plant. Specialist bees depend upon a specific genus or species of plant for food.

Overall, mining bees (Andrena) is an early emerging genus. Other genera of bees become active at various points throughout the year. Being aware of this timing can help one observe and identify bee species, which is why I compiled the bee activity timing chart below.

Factors in Native Bee Activity

To get a sense of the timing for bee activity, it helps to distinguish between social bees (primarily honeybees and bumble bees) and solitary bees. There are some genera that do not fit neatly within either the social or solitary categories.

Honeybees (weather and hive health). Honeybees live in hives that have some activity year-round. During cold seasons, the hive’s worker bees may venture out on certain days when the temperature is in the mid-fifties. Because there are many worker bees in a hive, there may be a noticeable number of them out foraging.

Bumble Bees (weather and colony growth). Bumble bee colonies/nests die out at the end of the season, with only one new fertilized queen to survive winter. Adults shelter in the ground, leaf litter, or cavities. During cold seasons, queens may become active and leave their shelter on warm days during cold seasons to forage. Fewer bumble bee queens will be seen on these days than honeybee workers. On cool days, bumble bees can also vibrate their bodies to warm themselves. When warm seasons arrive, queen bumble activity will become constant and gradually increase as the number of adults in the new nest grows.

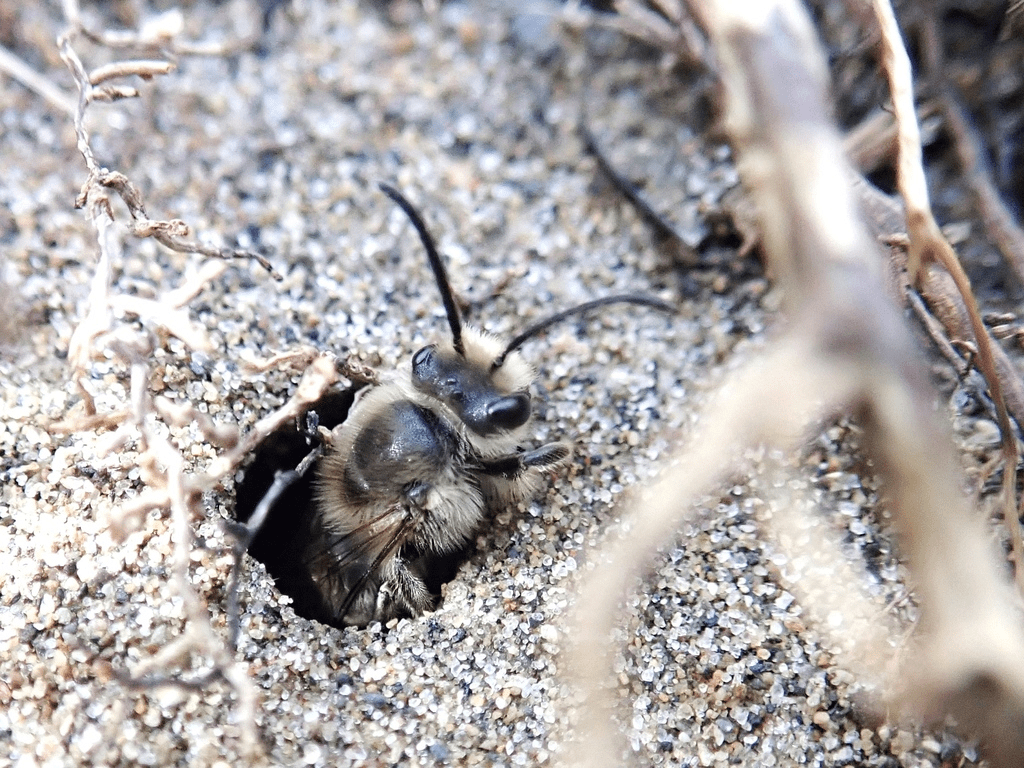

Solitary Bees (weather and biological clock of pupae). Most Ohio native bees are solitary in nature. Female bees lay eggs with food provisions in nests divided into cells. Some genera nest in the ground and others in cavities. Different bee genera use distinctive cell separator materials such as mud, leaves, and resin. Adult solitary bees do not overwinter, only pupae in the nest cells do. Solitary bee activity in a new year begins when pupae develop into adults. This is triggered by a combination of weather conditions and the bee’s biological clock. Since pupae of a species are generally on the same clock and there is no colony to develop, the level of activity for a species tends to jump.

Ohio Native Bee Activity Timing Chart

I created this chart of when various genera of Ohio native bees are active based on The Bees of Ohio: A Field Guide by the North American Native Bee Collaborative.(1) The Bees of Ohio is a helpful guide with an illustrated terminology of bee anatomy and specific information about each genus with photos to help in identification.

I compiled the individual species activity times into an overall timing chart. One of the Bees of Ohio authors has reviewed my composite chart. In the chart, the darker the green the more bee activity for that month. Each line in the chart is a different native bee genus. These are sorted from the genus with the earliest activity to those with the latest.

The earliest peak of bee activity is in April when solitary mining bees (Andrena), cellophane bees (Colletes), and mason bees (Osmia) emerge.

Keng-Lou James Hung, iNaturalist

https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/12116014

Rick Barricklow, iNaturalist

https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/156976160

Social bumble bees (Bombus) ramp up to a peak in July. Solitary leaf-cutting bees (Megachile and Coelioxys) also peak in July. Some of the latest bees are solitary green bees (Augochloropsis and Augochlora) that peak in August. Apart from their peak, many bees continue some level of activity into October and some even into November.

Additional Resources

I should mention a couple of additional resources…

If you want to track when and where in Ohio bees are being observed, check out the Ohio Bee Atlas project on iNaturalist. There is a map of observations so you can see what is happening in your area plus photo galleries of observations. If you are an iNaturalist member, you can join the project and contribute your observations. Submitting photos to iNaturalist for identification and contributing data for research is a great way to learn about bees and other insects.

Olivia Carrill and Joseph Wilson’s Common Bees of Eastern Norther America is a great field guide to learn about native bee species and to help with bee identification. Their earlier book, The Bees in Your Backyard: A Guide to North America’s Bees, is also a great reference book.

References

(1) North American Native Bee Collaborative. 2017. The Bees of Ohio: A Field Guide. Copyright Public Domain. https://www.co.portage.oh.us/sites/g/files/vyhlif3706/f/uploads/bees_of_ohio_field_guide.pdf

(2) Carrill Olivia Messinger and Joseph S. Wilson. 2021. Common Bees of Eastern North America. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press. https://worldcat.org/en/title/1284794921

(3) Wilson Joseph S and Olivia Messinger Carril. 2016. The Bees in Your Backyard: A Guide to North America’s Bees. Princeton Oxford: New Jersey: GB : Princeton University Press. https://www.worldcat.org/title/1034785970

Photos by Randy Litchfield unless otherwise noted

© Randy Litchfield, some rights reserved (CC-BY-NC)

Great newsletter! I learned a few things!

Thanks for the positive feedback!

Hi Randy and Terri! I always enjoy reading these blogs and even though I’m not able to do much lately, I sure do like living vicariously through you! Hope you, Erin and her family, are all well!

We are doing well! Thanks for following the blog!